The topic is not often mentioned at the dinner table or boardroom, but for those with spinal cord injury (SCI) or lower body paralysis, the ability to go to the bathroom ranks high on the list of every-day desires.

“Most people think about the wheelchair,” says Dennis Bourbeau, PhD, an investigator for the FES Center in Cleveland. “But if you talk to someone who has had a spinal cord injury for more than a couple years, they will say: ‘This wheelchair is fine. It’s my legs. If you could help me walk, of course I would take that, but that is not in my top priorities.’

“For people with paraplegia, number one is sexual function. Number 2A and 2B are bladder and bowel function,” says Bourbeau, a Biomedical Engineer at Stokes and Assistant Professor of Physical Medicine and Rehab at CWRU.

Driving a solution

All reside under one umbrella: Pelvic health. In our culture, that subject sometimes is taboo. It shouldn’t be. For those living with it, the lack of bladder, bowel and sexual function are a daily reminder of their condition, what they can and cannot do. Some of the solutions for bodily functions that most take for granted are, at best, unpleasant and difficult. FES Investigators drive the research in search of solutions.

The FES Center propels the work of scientists, engineers and clinicians in the use of Functional Electric Stimulation (FES) to improve the lives of those with neurological or other musculoskeletal impairments. The Center brings investigators together to advance the science, research and development of devices to help those with medical challenges – among them pelvic function, post-stroke limitations, chronic pain or movement after paralysis.

Bourbeau, Steven Brose, DO, and Ken Gustafson, PhD, are national leaders in the area of pelvic health, and thrive in the FES atmosphere of collaboration in search of solutions. FES works via a consortium of five nationally recognized institutions: the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center, Case Western Reserve University, MetroHealth Medical Center, University Hospitals and the Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute.

Gustafson, the Associate Director of Research & Education at the FES Center as well as an Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Urology and the Associate Director of the Neural Engineering Center at CWRU, points out that 15 million Americans deal with some type of bladder dysfunction. Some cases are so severe it keeps them from going to their kids events, or in some instances makes them afraid to even leave the house.

“There are not enough people doing the research,” Gustafson says. “But if you go to the drug store and walk over two aisles from the headache medicine, you’ll find a whole aisle of over-the-counter products to deal with it.”

Dr. Brose, the Chief of the Spinal Cord Injury and Disabilities Service at Syracuse VA Medical Center, works through the FES Center in his research. He marvels at the willingness of Veterans to take part in studies in hopes it will help their peers.

His clinical research has focused on finding a solution to bladder incontinence. One thing Bourbeau, Dr. Brose and Gustafson frequently hear from patients: “I want to go the rest of my life without having an accident.” Many people currently use catheters, which can lead to challenges with insertion and possible urinary tract infections.

The investigators have developed non-invasive electric devices that are controlled by a small remote control used by the patient. When the urge to urinate is felt, the research participant can hit a button, which reduces the need to go.

“This approach,” Dr. Brose says, “involves electrical stimulation of the genital nerves. It affects a neural circuit that relaxes the bladder, which allows the bladder to hold more urine, improves continence, and allows patients more time to get to bathroom.”

The investigators have a little bit more than one year left on a study that has sent nine patients home with the device for a year. He says he’s hearing good things.

“I had somebody come into the hospital with the device for his annual assessment,” Dr. Brose says. “He wanted me to let him keep using it in the hospital.”

His emphasis is on understanding the neural physiology of the pelvic area, then building the appropriate electrical device to address issues. Or as he says: “To let people regain their independence and dignity.”

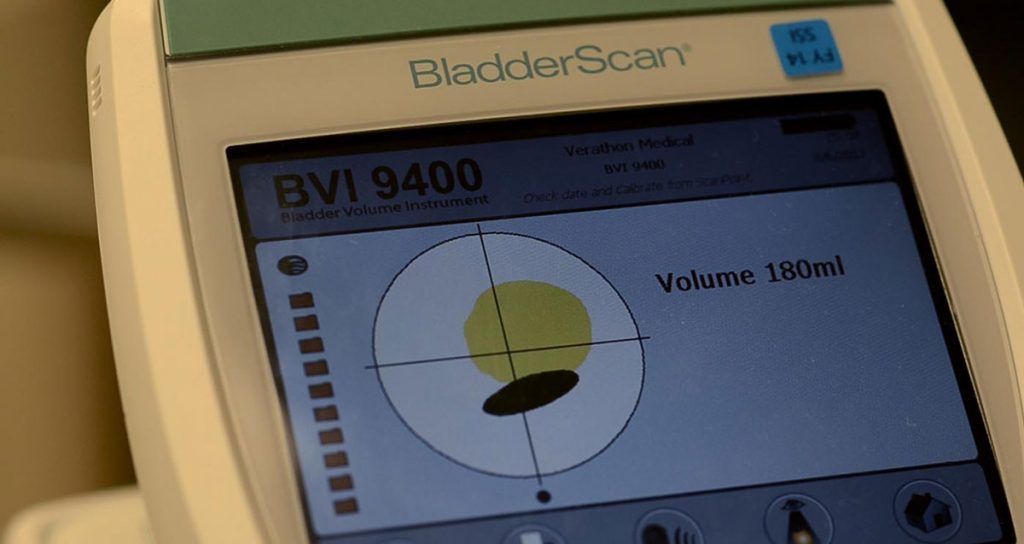

They started a clinical trial in January of 2021 that involved sending research participants home with what he calls a “bladder pacemaker” that they could control themselves.

“You can literally hit a stop button when you feel you have to go,” Gustafson says. “It gives you time to finish an email or whatever you’re doing, time that some people normally would not have.”

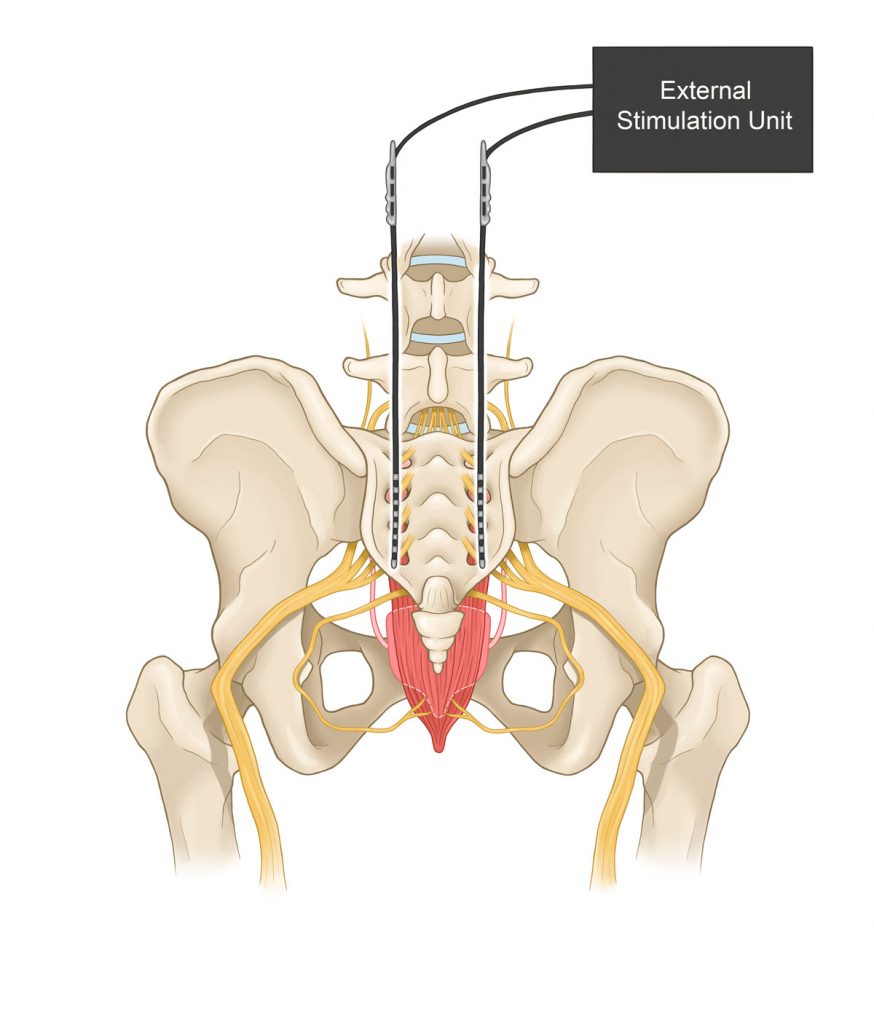

Bourbeau’s emphasis is on stimulating the genital nerve branch of the pudendal nerves. He also is implanting electrodes on the sacral spinal cord with what he calls an electrical version of a chemical block, which he compares to anesthesia at the dentist, and relax the muscles around the urethra. The goal is to achieve bladder emptying without use of a catheter.

Expanding the studies

Bowel function is the next challenge. Bourbeau says that those with SCI empty the bowel during a set routine, and hope there is no incontinence in the time between emptying. The routine could take place once a day, twice a week, or less frequently.

“There are people who will empty their bowel once a week and it will take one to four hours,” he says. “The more usual is once every day or two, and it will take 30-to-60 minutes.”

Methods to empty the bowel are not the most pleasant topic – Dr. Brose says today manual methods are used to cause a reflex. Dr. Brose and Bourbeau are early in research to bring about the same effect through stimulation.

Research into bowel function takes longer because that area of the body is complex. Bourbeau says there is less basic science in the bowel than the urinary tract, though there is new information and understanding developing daily. However, because the bowel moves slower than the bladder, it’s tougher to monitor and measure.

That being said, Bourbeau says those funding research into bladder function are encouraging him to proceed in studying the bowel.

“There is an overlap in the neural pathways controlling the bladder and bowel,” he says. “So it’s reasonable to believe that if our stimulation approach affects the bladder system it will also have an effect on the bowel system, depending on where we put that electrode.

“I’m just so excited that we’re getting bowel function into our repertoire.”

Research into sexual function could follow.

Bringing solutions home

Gustafson now sees other FES investigators asking about using the devices the pelvic team has developed in their research. He describes the FES Center’s philosophy as having “one key” – meaning that one key opens all doors, which leads to collaboration.

One use for the electrical device he’s developed is with amputees, to help them with sensation in the hand or foot, which helps provide better grasp or balance.

Every one of the three investigators is focused on going beyond the lab research to translational research, which means taking research into the marketplace and clinical environment, to bring real help to real people.

Science drives the research; the heart drives the science.